by Malcolm J. Brenner, B.A.

Part I: Feelings, Ohhh Feelings…

Part II: I’m Looking At The ‘Phin In The Mirror…

In Part I, I discussed the Caldwells, a married couple of scientists who authoritatively declared, in their 1967 book The World of the Bottlenose Dolphin, “Dolphins are not little humans in wet suits.”

They said this in an attempt to lay to rest what they felt was rampant, emergent pseudo-science about the “intelligence” and “spirituality” of dolphins coming from the John C. Lilly/Paul Spong camp of non-marine-biologist dolphin researchers, who experimented with then-rampant psychedelics, played jackhammers (Lilly) or wine glasses (Spong) to their subjects, and communed with them — psychically! (Or so they claimed.)

This series discusses some of the many striking similarities we DO share with dolphins, in this essay, self-recognition and self-awareness.

If David and Melba were alive today, I wonder how they would dismiss these similarities? Like debunking astronomers who claim, without actually researching, “No astronomer has ever seen a UFO,” (Jacques Vallee, J. Allen Hynek and Carl Sagan come to mind, among others), marine mammalogists come up with all kinds of fantastic explanations for the advanced reasoning capabilities displayed by dolphins, and their insights into situations, especially power-structures, even human power-structures, which must be very similar to their own to be recognized as such!

About 25 years before the two scientists who ran the mirror experiment arrived on the dolphin scene, a former atomic physicist named Horace Dobbs took to SCUBA diving with Donald, a “lone wolf” dolphin who hung out in the cold waters off Cornwall, in southwest England. He wrote a book about his experience, Follow a Wild Dolphin, and in it he described what happened when he introduced Donald to his mirror image. The following film shows the results better than I can describe them!

In the film, Donald seems perplexed, and rightfully so: his eyes are showing him something threatening (another male dolphin) that his echolocation cannot get a lock on! What appears deep to his vision is merely a thin, flat panel when he plexes it (a term I have come to use as convenient shorthand for a dolphin using echolocation to locate or identify an object or person). So, in frustration, he gives it a good whack with his snout, sending the shattered fragments to the sea floor, where they now glint back at him malevolently from many sides. He has, in his frustration, only made the problem worse!

Score: Mirror 27, Dolphin 0! Round Two…

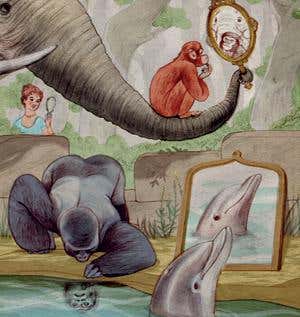

Self-awareness, or sapience — being able to think about your own thoughts — is rare in the animal kingdom. It was assumed, for the longest while, that no animal other than Homo sapiens possessed this characteristic, which is most eloquently expressed by recognizing that the face we see in the mirror is our own!

The dolphin-in-the-mirror experiment was definitively conducted in 2001 at the Baltimore Aquarium by two perceptive scientists, Lori Marino and Diana Reiss, for their joint PhD. project on animal cognition. By covering the mirror and marking the animal subject in an out-of-the-way place with a harmless grease marker, the two scientists were able to watch to see if the subject examined itself when the mirror’s cover was removed, a sure sign it knew the reflection was of itself, and not another threat or rival! (https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.101086398) Their experiment is rightly famous!

As an example of the lack of this ability to recognize one’s reflection, I will relate the plight of a male cardinal, whose nest was perilously close to a parking lot at Babcock Ranch, where I worked as a tour guide. The bird wasn’t in any danger from the cars; however, their outside rear view mirrors were filled with a dreaded competitor, who was somehow always there whenever the cardinal stopped to take a look! I don’t know how many hours it spent fruitlessly battling this intruder, but it was pretty obvious that the instinct to attack things that resembled itself did not evolve in the presence of the looking-glass. Talk about a fruitless task! The cardinal never realized he was fighting his own reflection! He was trapped by instinct, a process that not only operates below cognitive thought, but long before it can get its shorts on!

Experiments with jungle-dwelling mammals show similar results. Leopards, gorillas, baboons, even most chimpanzees, all either attacked their own image in a stainless-steel mirror, or tried to avoid it. In short, we may say that the mirror aroused anxiety in them — I think that is anti-anthropomorphic enough to qualify as a valid assertion, don’t you? Only a few species of non-human animals showed consistent awareness of their mirror image, the ability to use the mirror to locate a mark on their bodies that they could not otherwise see, and examine it! Indian elephants and bottlenose dolphins were two of them. No surprise there, huh? Both have brains up to several times larger than human, with more folds on the substantial neocortex!

But among the NON-MAMMALS put before the mirror, several AVIANS — the last surviving category of DINOSAURIA! — showed critical mirror awareness, with brains roughly the size of shelled walnuts! How the ding-dang-doodle do they manage that with such tiny little brains? I refer to the Corvids, including magpies, crows and ravens, and the Psittacines, that is, the parrots and macaws, whose intellectual achievements have been shown to be closer to an 8-year-old child than to what we used to mockingly call a “bird brain!” Turns out we were unwittingly complimenting birds, much the way Motorola complimented Sony when a Motorola employee bought the first transistorized shirt-pocket radio!

checking out the photographer! Parrots are long-lived, often outlasting their humans!

©2022 Malcolm J. Brenner

One factor shared by all, save one, of these creatures (the pachyderms), is the desensitization, and even total loss, of the brain regions devoted to smell. Most birds have no sense of smell, nor do any of the cetaceans; they don’t have the brains for it! Smell to them is like echolocation to us, a theoretical concept.

The olfactory sense must have been the last, and most recent, to evolve in the Permian period, when insects and amphibians were first colonizing dry land. While life remained immersed in water, the sense of smell was subsumed under the sense of taste. It’s pretty much a moot point to me whether sharks, for instance, taste blood with their tongues or “smell” it with some kind of olfactory apparatus associated with the nostrils, they can reportedly detect blood in the water at 1:1,000,000 dilution!

That’s one part in one million, sucker. Keep swimming, that shark needs exercise!

(NOTE TO SELF: Check to see whether sharks do, indeed, have nostrils, or whether they smell with their gills. We wouldn’t want to lead people astray, would we? Oh, no, no, NO! Inaccuracy! Dishonesty! Guilt!)

(ANSWER: Yes, indeedy, they do! But the nostrils have no connection to respiration! See https://www.fau.edu/newsdesk/articles/shark-snout-study for all the dirt on shark sense of smell!)

This specific change in the cetacean and human brains will the the subject of Part III of this article, Can’t You Smell That Smell? It should be published in the next month, if I keep feeling as forward-moving as I do now… of course, my progress is only measured by how many steps backward I must take for each one forward!

Another interesting feature of these self-aware creature’s brains is that they feature a special type of nerve cell, or neuron, that doesn’t appear in the brains of un-self-aware creatures. It’s called a von Economo neuron, after the 1926 discoverer, or more casually, a spindle cell, based on its shape.

Photos from Smithsonian Magazine. Whaddya think, I sliced up somebody’s brain? Sheesh! “It’s okay, he wasn’t using it anyway!“

Von Economo neurons aren’t found in the brains of monkeys. They are found sparsely in the brains of primates, somewhat more densely in the brains of elephants, more densely in cetacean brains and MOST densely in human brains! “Aha,” you exclaim, “human exceptionalism shows itself once again!” But I must demur! More than the basic fact of density/cm3, it’s how often these neurons get used that determines their degree of functionality! You can own a Cray supercomputer, but if you never turn it on, you’re going to do better math with the Calculator app on your iPhone!*

( * DISCLAIMER: The author does not own any stock in Apple, nor does anyone in his family work for Apple or have an interest in Apple. He is simply the humble owner of an iPhone, and appreciates the fact that it was so damn easy to figure out! Even for an all-thumbs 1950’s child like himself, yes!)

What exactly these von Economo neurons do is something of a mystery, but it is thought that they help transmit signals quickly across uninvolved regions of the brain, the idea being that since they only have one dendrite, they are able to respond more quickly than typical neurons, with multiple dendrites. They seem to have some effect on one’s sense of self, self-image and relations with others, but what shows most clearly is their lack. John Allman, a brain researcher at CalTech Pasadena, says “It is very clear that the original target of the disease (frontotemporal dementia) is these cells, and when you destroy these cells you get the whole breakdown of social functioning. That’s a really astounding result that speaks to the function of the cells about as clearly as anything can.”

In other words, what the von Economo neurons do, and how this affects the behavior of their owner, is not clear, and the brain-boffins are whistling past the graveyard! I mean, I read several Inter-Web articles on the damn things, and neurologists can barely agree on where these cells are found (between your ears, duh, but in only ONE LAYER of the brain), and whether they are REALLY different brains cells, or just look different.

(I DIDN’T KNOW BRAIN CELLS DISCRIMINATED BASED ON APPEARANCE, BUT I GUESS THAT’S THEIR JOB, EH?)

So what does this all boil down to?

Simply this: there are valid, biological reasons why dolphins appear to show such unusual animal behaviors as mutual aid-giving, social learning, and collective, cooperative behavior — like when the dolphins of Manaus, Brazil, help the local fishermen net fish, and eat what spills out! Parsimonious scientists suggest that these are just “spillover” behaviors, that the dolphins are reacting more-or-less instinctively toward us, without any real consideration of who or what we are.

But the fact is, most dolphins, even wild ones, show an intense, personal interest in us, when they get the chance. They don’t flee, like most wild animals do in the presence of humans; instead, they interact with us in a curious, often playful way, and sometimes even challenge us to play their games, make their noises, share their food, or even move utterly beyond the bounds of being human! And frankly, the idea that they are doing all those things INSTINCTIVELY…

…well, and purely confidentially, I think it stinks! But we’ll deal with that in Part III.

Image: “The Consciousness Connection,” by Jonathan Burton, New Scientist, 2012

COMING NEXT: PART III, Can’t You Smell That Smell? How dolphins lost their noses and part of their brains but gained blowholes! STAY TUNED, FELLOW DOLPHIN LOVERS!

###