“YOUR GOD ISN’T BIG ENOUGH:”

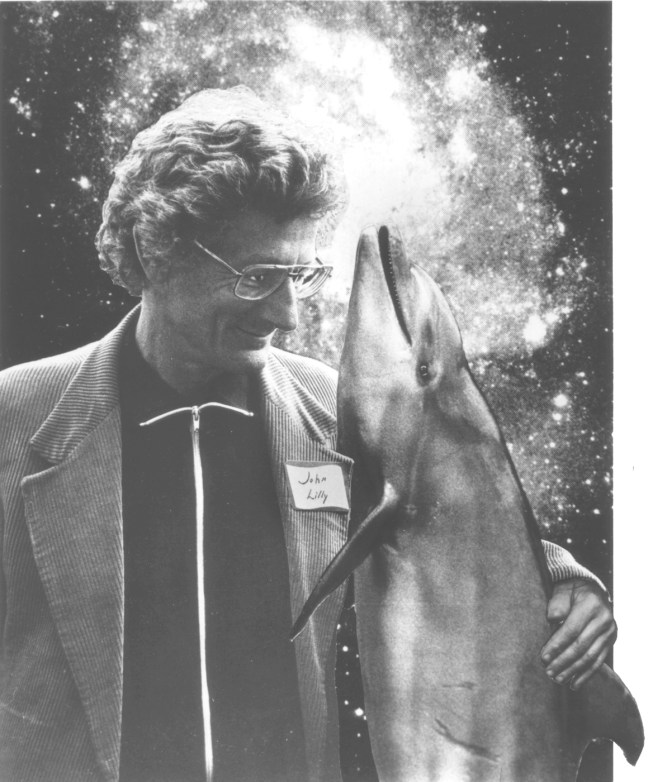

An Interview with John C. Lilly

By MALCOLM J. BRENNER, FUTURE LIFE #20, August 1980

John Cunningham Lilly is that rare breed of scientist willing to talk openly about his belief in God—or, more precisely, his belief in his mind’s ability to simulate God with a reasonable degree of accuracy. An M.D. with psychiatric training, Lilly is best known for his sometimes controversial research on interspecies communications with bottlenose dolphins, a study he’s pursued for over 25 years (Man and Dolphin, Mind of the Dolphin, Lilly on Dolphins, Communication Between Man and Dolphin).

A self-described “permissionary” possessed of a sometimes dangerously insatiable curiosity about the workings of the human mind, Lilly has also immersed himself in sensory isolation tanks (Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer, The Deep Self), experimented with hallucinogens and Sufi mysticism (Center of the Cyclone), deep dyadic relationships (The Dyadic Cyclone with Antoinette Lilly), and explored the fringes of his own consciousness in The Scientist, a “novel autobiography. ” With Antoinette Oshman Lilly, his wife, partner and “soulmate,” he has started the Human-Dolphin Foundation headquartered in Malibu, CA.

Lilly is currently conducting tests at a California oceanarium on a new computer program designed to overcome the difficulties of human-dolphin communication, Project JANUS (Joint Analog-Numerical Understanding System). Dr. Lilly was interviewed during the Second Annual Mind Miraculous Symposium of the Church of Religious Science in Seattle.

MB: How did the sensory isolation tank work you did at the National Institute of Mental Health in the early ’50s lead you to the dolphins?

JL: I began that work at the National Institute of Mental Health, just wondering what would happen if you freed yourself up from a lot of external stimulation, and lowered all the inputs to the lowest possible level; what would happen to your mind under those conditions? It was just curiosity, just that sort of extracurricular activity one does in one’s general research; they didn’t even know I was doing it on my own time. I was working on monkey brains, and I’d go off to the tank and come back to the lab with a different perspective.

When they got wind of this, they asked me to get deeper into it. I was floating around in the tank in 1954 and started wondering about these things. I was beginning to find that my freedom of thinking was immensely increased, freed up from the necessity of temperature and gravity and light and sound and all that. There was this huge freedom of imagination, of experiencing things inside, which isn’t there any other way that I know of. And I was just wondering whether there wasn’t somebody floating around 24 hours a day their whole life who might be experiencing this all the time, and who would consider it absolutely normal.

So I began to talk to various people about dolphins, Pete Scholander and various others, and got interested. And then the brain thing came in, looking at their brains, seeing if the substrate for mind was there. And it was.

MB: When you were doing that early tank work, did you have any of the type of apparent “contact” experiences with other civilizations or creatures from other planets or dolphins you wrote about in Center of the Cyclone?

JL: No, there was a period there from ’54 to ’58, when I left NIMH, where the dolphin work and the tank work were overlapping. I began to see that the dimensions of mind were far greater than I’d been assuming they were, and were assumed by psychiatrists and psychologists. And I didn’t own up to it at the time it was happening. I didn’t own up to it until I was free to set up a tank in the Virgin Islands without all this government support and financing.

In fact, none of the tank work was ever directly supported by government grants; it was all done extra-curricularly. And I didn’t realize how important it was until I began to see how my thinking was changing as a consequence of these experiences, and the kind of vastness of the whole business. The mysteries of the mind… I was really immersed in them. And I began to see that the dolphin mind was probably far greater than our consensus reality allowed our minds to be. That’s why I want to communicate.

MB: In the early ’60s, you got a lot of publicity from media like Life and Newsweek, and there was a big surge of interest in the possibility of interspecies communications with dolphins. Did that make your work more difficult? Did it make other scientists more skeptical of you because you’d “gone public” before your results were confirmed?

JL: That was unplanned; the results began to come out in sources like The Journal of Acoustical Research & Engineering, and the media got interested. They were reporting on what we were doing; we weren’t seeking them. Now, as to what you mean by “other scientists,” I don’t know.

MB: Other marine mammalogists.

JL: Well, I’m not a marine mammalogist. Never have been. I’ve never been a cetologist or a delphinologist in the narrow sense that those people call themselves. I’ve never approached dolphins that way; I’ve always approached them from the standpoint of mind. They won’t even assume dolphins have a mind, so right off the bat we’re in entirely different domains of discourse. I’ve never felt that conflict they’ve felt; it’s their conflict, not mine.

MB: Between the period in 1968 when you released your dolphins and the beginning of Project JANUS, did you get discouraged about your dolphin research?

JL: Well, the time wasn’t right. The computers weren’t fast enough, small enough, and didn’t have large enough memories to do the job I wanted them to do.

MB: Between Aristotle in 350 B.C. and the resurgence of dolphin interest in the ’50s, due largely to your work, we have a terrible gap in our curiosity about these creatures. Why? How did we lose that closeness with the dolphins that the Greeks and some other ancient peoples had?

JL: The Mediterranean was much warmer in the time of the ancient Greeks, and they were much closer to the sea. And Aristotle was, I think, a kind of observing genius who got in contact with fishermen and people who were in close contact with the dolphins. And they must have had dolphins in captivity, caught in shallow pools or something like that, and they just were free with them, spoke to the dolphins, and the dolphins spoke back. It was this intimate contact, which we reproduced in experiments back in the ’50s and ’60s, which led to Project JANUS. In the modern oceanaria there isn’t much of this. It’s beginning, but it’s not there yet.

It’s shallow-water intimacy with the dolphins. Humans in deep water are pretty ineffective; dolphins in extremely shallow water are pretty ineffective, but you have to balance those two things together, and I think that just by chance the Greeks did that.

If you follow the history of humans since then, they got away from that, away from the sea. They stuck to deep water when they went to sea, and this tidepool thing just disappeared. The whole attitude—the belief systems and so on—were counter to it. The Jewish-Christian-Muslim ethic took over, and we totally moved away from that free-floating thing the Greeks had. The interest in dolphins as reincarnated humans and all that disappeared.

MB: One point Robin Brown makes in his book The Lure of the Dolphin is that, in terms of their morals and their scruples, the Greeks actually placed the dolphins above their own gods! One can detect a lot of the same thing in your writings—that there is a morality in the dolphins that prevents them from harming humans, under most circumstances.

JL: Ethics. It’s taught. The Greeks worshipped dolphins; they had a dolphin cult. Temples to them were found in the Negeb desert in Jordan, for instance. It was a very, very different socialized belief system which disappeared. And the modern point of view, which we started going after, was just sort of empirical approaches to them based on all sorts of considerations the Greeks didn’t have, such as their large brains, their behavior in captivity—those sorts of things.

MB: Do you think the Greeks kept dolphins in captivity for religious purposes?

JL: Yeah, I think that the original Delphic oracle, before the gal who was breathing vapors from a vent in a volcano, was probably a seaside thing that was never written up, in which certain people began to use dolphins speaking in air as oracles—spiracle oracles, you might say. But that’s speculation.

MB: You said earlier that you weren’t expecting a “breakthrough ” at this stage of Project JANUS. Is it fair to ask what you are expecting?

JL: A lot of hard work, one step after the other. For a while we’re going to have to be really restrictive, because it’s going to be a lot of hard work by a very few people. It’ll be a while before we can get our feet on the… get our feet wet. We don’t talk about “getting our feet on the ground’’ any more.

MB: What level of communication do you think you can achieve with the equipment you now have?

JL: I don’t know; that’s open-ended. Imagine starting out with humans, say, somebody that didn’t know your language, with the JANUS program. Now, in the JANUS software there is a program which chooses alternate tables of frequencies; one for the dolphins, based on their frequency discrimination curve, and one for humans, based on ours, and we’ve been working with humans on this. Turns out that there are new gestalts that develop. For instance, if you type H-E-L-L-O and activate JANUS, it comes back with the frequency for H, and the frequency for E, the frequency for L, and repeats it, and the frequency for O. This makes a little tune. And that word has been used so many times around the lab that everybody knows when the computer’s saying “hello!”

MB: Like the tones on a touch-tone phone?

JL: No, it’s not, because the touch-tone phone is designed so you can’t do that. Each button has two tones, so a pure tone won’t affect it; they’re fouling you up on that. It doesn’t have the clarity it would if they were pure sine waves. The basic idea is quite different, actually. What does the phone have—12 buttons?—of which we only use 10 for normal dialing. And we have 48 buttons, each one of which gives you pure sine waves, and each of which you can remember, without trying to untangle multiple frequencies. So you’re hearing pure tones the way you would keying a synthesizer with only one oscillator instead of three.

MB: But you type in ”hello” and what comes out is a characteristic tune?

JL: A gestalt, right. An easily recognizable acoustic gestalt. It looks as though we will be doing a very peculiar job, which reminds me of Herman Hesse’s Bead Game in Magister Ludi, in which they’re combining mathematics, logic and music in a very complex game. And that’s what we’re doing, really—developing a whole new vocabulary in the acoustic sphere which is representable by ordinary typewriter script. John Klemmer came up and started playing with it, and he wants to write music this way. So now you can type out music on an ordinary typewriter. For instance, we worked out what that theme they used in Close Encounters of the Third Kind means, where they start communicating with the aliens. You have these five notes. Well, it turns out that on the JANUS program those are S, U, Q, B and K.

MB: Not much of a message…

JL: Yes it is, because anybody who’s seen CE3K recognizes it instantly. So you’ve got all these new degrees of freedom in the acoustic versus the symbolic typing. For instance, we can type out a very long message on JANUS, put it through a phone line, bring it back into JANUS, and JANUS will type out what those sounds mean.

MB: Why did you decide on a computer system, rather than a frequency-shifting real-time vocoder, as described in Mind of the Dolphin?

JL: I wanted a system that is more easily, reliably reproducible than a human talking.

MB: Punch a key on the computer and you always get the same sound out the other side?

JL: Right. It’s an elementary approach where you have a chance of learning new things about the dolphins’ perceptual systems. Then you can eventually design something that’s much more sophisticated, based on the basics you discover with this approach.

It’s what you might call a survey apparatus. You’ve got a general purpose computer you can reprogram; general purpose interfaces you can reprogram through the computer so the voice can be reprogrammed, the ear can be reprogrammed. So you can try different approaches. We’re initially starting with pure sine waves as the output to the dolphins, from about 3,000 to 40,000 Hz., and varying the duration. We’ve had to modify our initial guesses to match their frequency-discrimination curve a little better. We may then add clicks, continuous FM whistles and tones.

This is just the initiation, the opening-up of the whole field. JANUS is the first system that has total round-trip feedback, where the computer has a voice and ears, instead of dictating to the dolphins, as some other researchers are doing. They ignore what the dolphins have to say, mainly because they don’t have the sophisticated approaches that allow the computer to hear and interpret the sounds.

MB: Will the computer have a memory system that will allow it to build up a vocabulary of dolphin sounds?

JL: Not initially, though we will be building that up through the transitional symbolic vocabulary. We’re starting with 48 symbols, which is a sufficiently large population so we can get a large number of different strings. English has 44 phonemes in it. That should appeal to the dolphins; they like long strings and complex strings, a great variety of sound. And we’re covering their frequency-discrimination curve where they’re best at it, the way English covers the human curve.

MB: So the objective of JANUS is to set up an intermediary language between humans and dolphins?

JL: Yeah. Now language… we’ve set up a code system to develop any number of languages, and we’ve tried to arrive at a reproducible standardized system, which you can’t do with a vocoder, because of the variations in individual voices… yet vocoders have degrees of freedom this doesn’t have. The vocoder will respond to different kinds of voices, and the dolphins will answer in different voices. But here, we’re requiring a rather narrow slot in performance on their part, which we can record and follow.

So at one end of the spectrum you have this rather rigid system we’ve devised, and at the other you have a somewhat more flexible system. We’ll probably meet in the middle somewhere, so there’s more flexibility and it’s more like a voice.

MB: Now, if I were a dolphin inputting into JANUS, would I have to input in the same pure sine wave tones JANUS puts out to me?

JL: Well, we had a gal who put a pair of headphones on—we used the human scale on this —and she had a Moog synthesizer, the keys on it marked like a typewriter, so you can tell just what you’re typing out. She was typing things in, listening to the tune, then singing it back into JANUS through a microphone. And she could make the transfer; she would type out words on the synthesizer, hear them, then with her own voice sing to JANUS, and JANUS would type out the same thing. But she’s an expert singer.

MB: So you don’t anticipate nearly as much trouble on the dolphins’ part as it would be to phonate in air, as you were doing earlier?

JL: Oh, no, this is all underwater. Though they have started to phonate in air, mimicking JANUS’s output. Apparently they’re eager to learn.

MB: Have you received widespread public support for Project JANUS?

JL: Enough. We’ve always had just enough.

###

2 thoughts on “Interview: John C. Lilly, M.D. (Part 1)”